Encrypted Client Hello Defense Strategies - How Cisco Secure Firewall Tackles ECH

Introduction - The Security Visibility Crisis

Imagine staring at a radar screen that appears to be working perfectly—displaying normal patterns, showing no threats, giving you a false sense of security. But unknown to you, sophisticated aircraft are penetrating your airspace completely undetected. The radar is still on, the screen is still glowing, but you are completely blind to the real danger approaching. That's the reality facing network security professionals today as encryption technologies evolve faster than ever. Your firewalls are still running, your security stack is still active, but you're quietly losing critical visibility without even realising it - while threats move freely through your network.

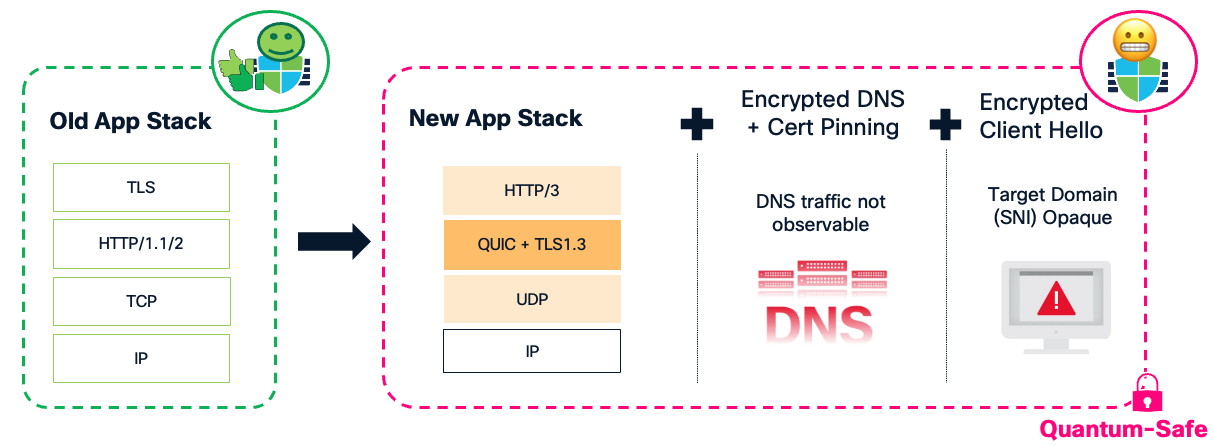

The stark reality:

- over 90% of internet traffic is encrypted with nearly half now using QUIC and bypassing traditional TCP inspection

- HTTP/3 adoption is accelerating, running exclusively over QUIC's encrypted UDP transport

- Encrypted DNS over HTTP/2, HTTP/3 and QUIC allows clients to bypass corporate DNS controls entirely

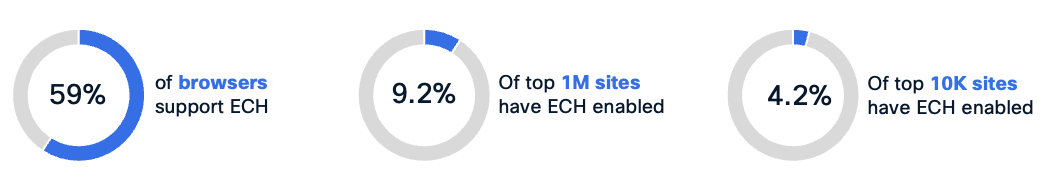

- 59% of browsers support Encrypted Client Hello (ECH), hiding destination information and eliminating the last piece of cleartext visibility in TLS/QUIC handshake

- 57% of browsers already use Post-Quantum Cryptography, future-proofing against quantum computer attacks

The convergence of these technologies - QUIC, HTTP/3, Encrypted Client Hello and Post-Quantum Cryptography -creates a cryptographic protocol stack that significantly decreases the capabilities of the existing security approach strongly based on network protection capabilities.

Without visibility, there is no security. And the new encryption stack is making us blind while our instruments tell us everything is fine.

Your security appliances remain operational, your policies stay in place, but the visibility that powers your security decisions is evaporating.

Among these challenges, Encrypted Client Hello represents perhaps the most significant threat to network visibility in the modern security landscape. Let's dive deep into what ECH is, why it matters, and how organisations can prepare.

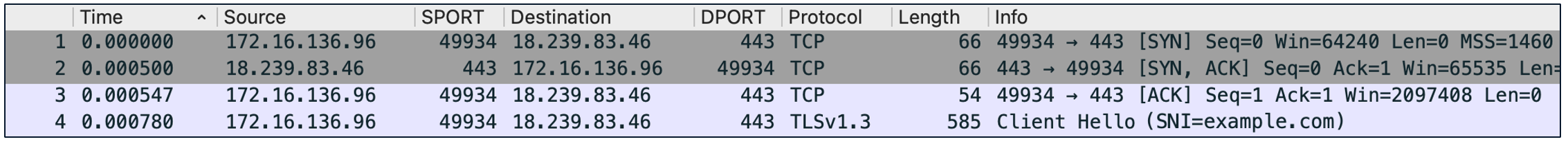

Why SNI Matters So Much

Before understanding ECH, let us recap what is at stake. The TLS protocol begins with a handshake message called the Client Hello, which historically has been transmitted in cleartext. This exposes metadata—including the Server Name Indication (SNI) - that on-path middle-boxes can observe and use for various purposes, including policy decisions for security or compliance reasons. The plaintext SNI leaks the target domain of a given connection allowing firewalls to perform their security functions despite the rest of the transmitted data remaining encrypted. The SNI extension appears immediately after the TCP three-way handshake during TLS negotiation, transmitted in cleartext and easily observable by any on-path device.

The SNI itself is unreliable by design since it can be easily spoofed or omitted all together, which is why network security devices don't simply trust it. Instead, they use it as initial intelligence and then validate the information through additional checks (such as comparing it against the server certificate with Server Identity Probe). This verification process is what makes SNI valuable for security: not as an absolute source of truth, but as a starting point for deeper inspection and validation.

Today's network security infrastructure relies heavily on the SNI extension, which drives most of what we've historically called "next generation" firewall security decisions:

- URL Category and Reputation filtering – blocking malicious or inappropriate sites

- Application identification – understanding what applications are allowed through the firewall

- Security Intelligence URL – blocking known malicious domains learned by Talos

- TLS Server Identity Probe – preventing SNI spoofing and improving decryption accuracy

- Selective TLS/QUIC decryption – deciding which connections need deep inspection

- Advanced inspection capabilities – IPS, malware protection, threat intelligence

Without SNI visibility, the critical security functions listed above become severely impaired or completely ineffective. As a result, the security devices remain operational, but an increasing portion of traffic is not subjected to deep inspection since it hides its real destination. Without proper understanding and preparation a network administrator might not even be aware of this fact, missing symptoms of security policy violations or a compromise.

The Impact of Encrypted Client Hello (ECH)

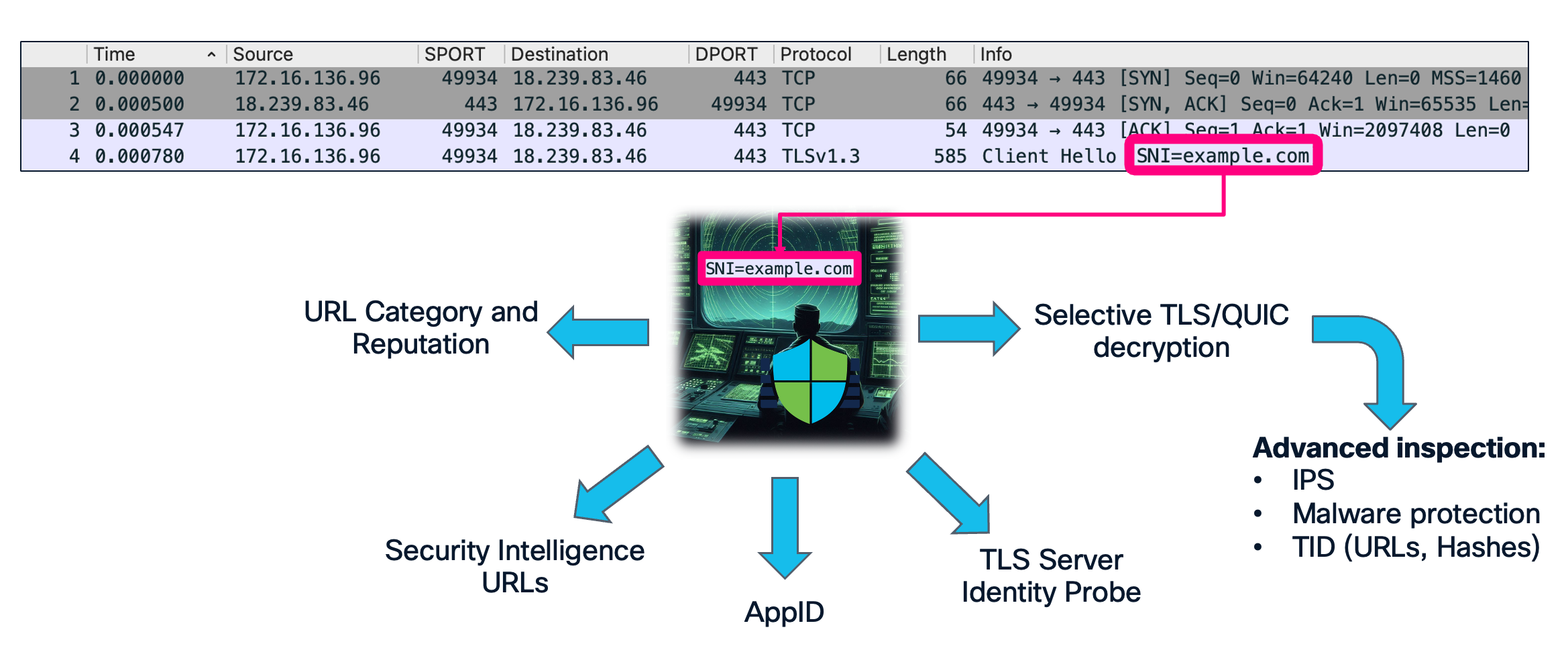

Encrypted Client Hello is the final piece of the puzzle designed to close what privacy advocates consider the "SNI security gap." ECH encrypts the Server Name Indication and other sensitive handshake parameters. By concealing this metadata, ECH helps protect user privacy, prevents targeted blocking of specific websites, and enhances overall internet security. While ECH was designed for legitimate privacy enhancement, it creates significant challenges to an organisation’s current security strategies based on network devices filtering traffic. ECH makes it impossible for network-based security appliances to see which specific website a user is accessing, creating a one to many relationship, where tens of thousands of web applications hide behind a single Content Delivery Network provider SNI.

When dealing with traffic protected with ECH the firewalls lose their ability to:

- Identify the real destination of communications

- Validate SNI claims against server certificates

- Make informed decisions about which traffic requires inspection

- Apply security policies based on destination context

- Perform selective TLS and QUIC decryption for deep inspection

The current adoption statistics on both client and CDN sides prove ECH an imminent and rapidly forthcoming concern. The infrastructure is ready on both the client side (browsers) and server side (CDNs) providing full ECH support. The protocol is at draft 25 and expected to be ratified as an official standard in the near future.

Cloudflare leads the innovation, being the first major CDN to fully support Encrypted Client Hello in their infrastructure—including their free plan, where ECH cannot be disabled. At the time of writing this article, 4.2% of the top 100K websites[1] and 9.2% of the top 1M websites[2] support ECH. On the client side 59% of browsers[3] including Chrome, Edge, Firefox and Safari actively use ECH out-of-the-box.

When Privacy Becomes Weaponized: Real-World ECH Exploitation

The visibility gap created by ECH presents an ideal opportunity for malicious actors to evade organizational security controls. As with other protocols in the past, every opportunity for stealthy communication is quickly adopted by threat actors seeking to bypass defences. Leveraging these techniques allows attackers to achieve their objectives with less effort and a smaller chance of detection.

A real-world malware threat was detected in early 2024 by researchers at NTT Security Holdings during their analysis of targeted attacks against Japanese organizations[4]. They identified sophisticated malware leveraging ECH for command-and-control (C2) communications.

"We identified a noteworthy piece of malware [...] distinguishing itself by leveraging Encrypted Client Hello (ECH) for its C&C communications [...] significantly harder to detect and block using conventional security products."

— Yuta Sawabe & Rintaro Koike, NTT Security Holdings

ECHidna leverages ECH to hide its network activity from traditional security infrastructure. The C2 traffic appears as legitimate connections to CDN infrastructure, while the real malicious host remains hidden behind the ECH facade. The use of Encrypted Client Hello bypasses security controls that could normally detect and block malware activity: domain blocklisting, URL filtering, or identifying suspicious traffic to selectively decrypt.

This is just a single real-world example, but history shows that stealthy techniques get adopted very quickly by the threat actor community. We can soon expect:

- New malware families incorporating ECH for C2 communication

- Ransomware groups using ECH to hide data exfiltration

- APT campaigns leveraging ECH for long-term persistence

- Commodity malware adopting ECH as a standard evasion technique

The ECHidna discovery demonstrates that ECH threats are not theoretical - they are already here. Organisations that haven't begun addressing ECH visibility gap might be already experiencing undetected malicious traffic.

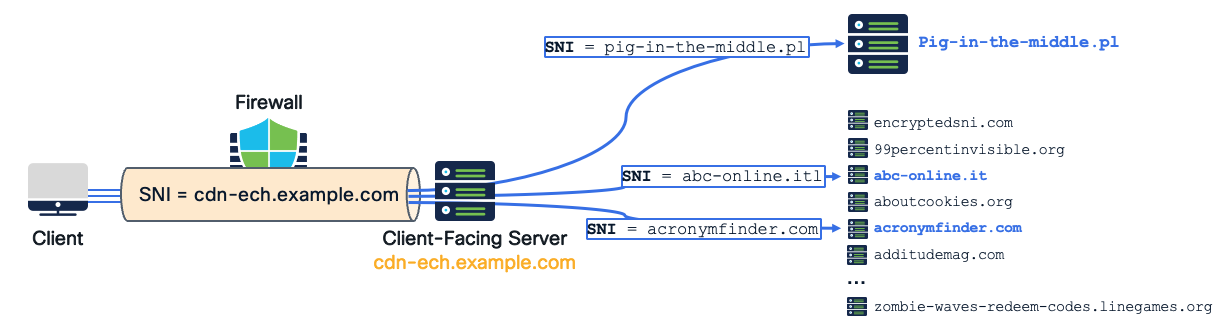

How Encrypted Client Hello Works Step-by-Step

To truly understand the threat ECH poses and how to defend against it, we need to understand the mechanics of how it actually works. The process is surprisingly elegant, which is precisely what makes it so dangerous.

Before diving into the technical flow, it's worth understanding just how accessible ECH has become. Setting up an ECH-enabled service is as simple as setting up a web server on the Internet and signing up for a free plan at a CDN provider that enables ECH by default - sometimes without the ability to disable it on free tier plans. This means thousands of websites can now hide behind CDN ECH infrastructure without any additional cost or technical expertise. The barrier to entry is effectively zero, which explains why ECH adoption is accelerating so rapidly.

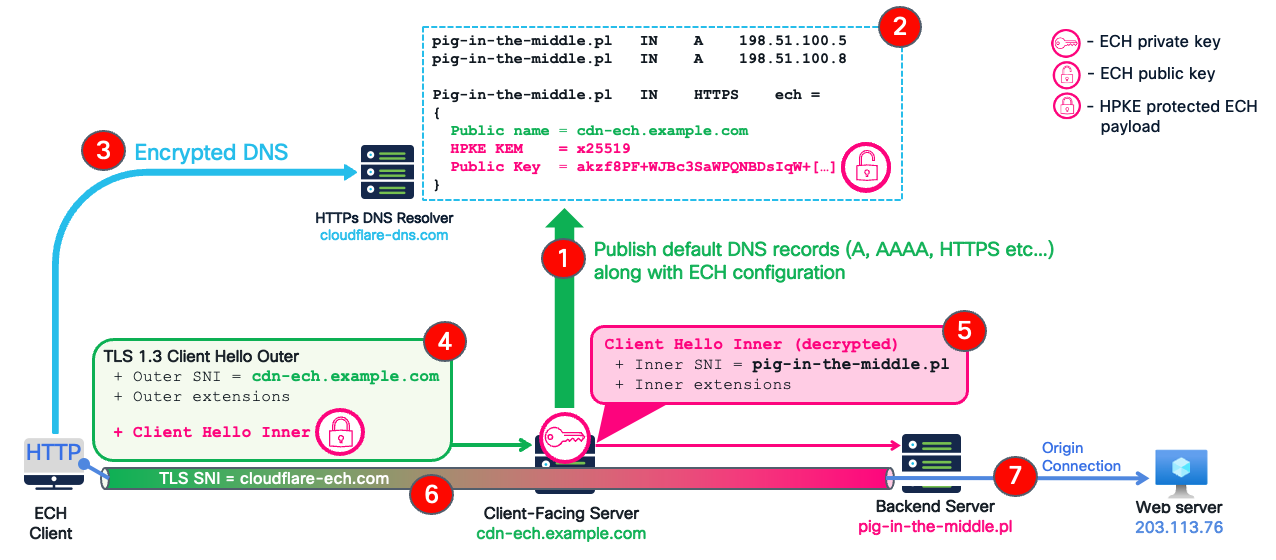

The diagram below illustrates the end-to-end Encrypted Client Hello flow between a client using a supported web browser and the "pig-in-the-middle.pl" test web server hosted behind one of the CDNs, providing ECH infrastructure out-of-the-box in their free plan.

-

DNS configuration publication - when a web server is fronted by and its domain delegated to an ECH-capable CDN, they automatically publish a set of DNS records resolving to CDN's infrastructure.

-

HTTPS record provides ECH configuration - in addition to the regular A and AAAA records, the CDN publishes an HTTPS record containing ECH configuration including:

- the public name of the ECH client-facing servers (e.g. cdn-ech.example.com)

- a public key for Hybrid Public Key Encryption (HPKE)

This ECH configuration tells clients how to reach the server through the ECH front-end without exposing to a middlebox security devices where they're actually going.

-

Client retrieves ECH configuration - when a user wants to visit pig-in-the-middle.pl, their browser:

• sends an encrypted DNS query (using DNS over HTTPS or DNS over HTTP/3) to a public resolver

• receives both the IP addresses and the ECH configuration

• now possesses the public key needed to encrypt the real destination

If your corporate security controls can't see or block this encrypted DNS query, you've already lost the first line of defense. The client now has everything it needs to establish a stealth connection.

Advanced threat actors may bypass DNS monitoring entirely by obtaining ECH configuration through alternative channels - by hardcoding it in the malware binary or retrieving it from seemingly benign public services (blog posts, YouTube descriptions, GitHub repositories etc...). This means that while DNS control is essential and effective against standard browser traffic and less sophisticated threats, it cannot be your only line of defense against determined adversaries.

- Client connects to CDN with dual Client Hello structure - with ECH configuration obtained in the previous step the client browser is now ready to connect to the CDN’s client facing server. This is where ECH gets particularly clever. The client creates two separate Client Hello messages:

- The inner Client Hello (Encrypted) – this contains the real connection information that a security device would want to inspect including the real SNI: pig-in-the-middle.pl. This inner datagram is encrypted with the public key obtained from DNS, creating what's called an HPKE (Hybrid Public Key Encryption) protected payload.

- The outer Client Hello (Visible) - This is what network observers including firewalls actually see and may use for security policy evaluation. The client connects to an ECH endpoint at the CDN provider exposing only generic TLS parameters and not revealing the real destination. Technically, this payload has the SNI of the public name of the ECH client facing server (cdn-ech.example.com), that could be hosting anything from thousands of different websites. This Outer Client Hello carries the encrypted Inner Client Hello as a TLS extension, opaque to any middle-box device.

- Edge server decrypts Inner Client Hello extension - When this TLS Client Hello reaches the CDN’s edge (the Client Facing server):

- the server decrypts the Inner Client Hello using its private key (corresponding to the public key distributed via DNS) and learns the real destination: pig-in-the-middle.pl

- The server forwards the decrypted Inner Client Hello to the backend server

The client-facing server only participates in the cryptography until it decrypts the initial Inner Client Hello. After that point, the entire encryption is between the backend server and the client. The ECH gateway essentially acts as a decoder and router - it doesn't remain in the data path for the actual encrypted communication.

- Finalising the TLS handshake - The backend server completes the TLS handshake using the clear-text Inner Client Hello with the real SNI (pig-in-the-middle.pl).

- Secure and stealthy connection established - the client browser connects securely and stealthily to the target server without revealing its real destination to anyone in the Internet, including your security infrastructure.

Encrypted Client Hello Detection Challenge

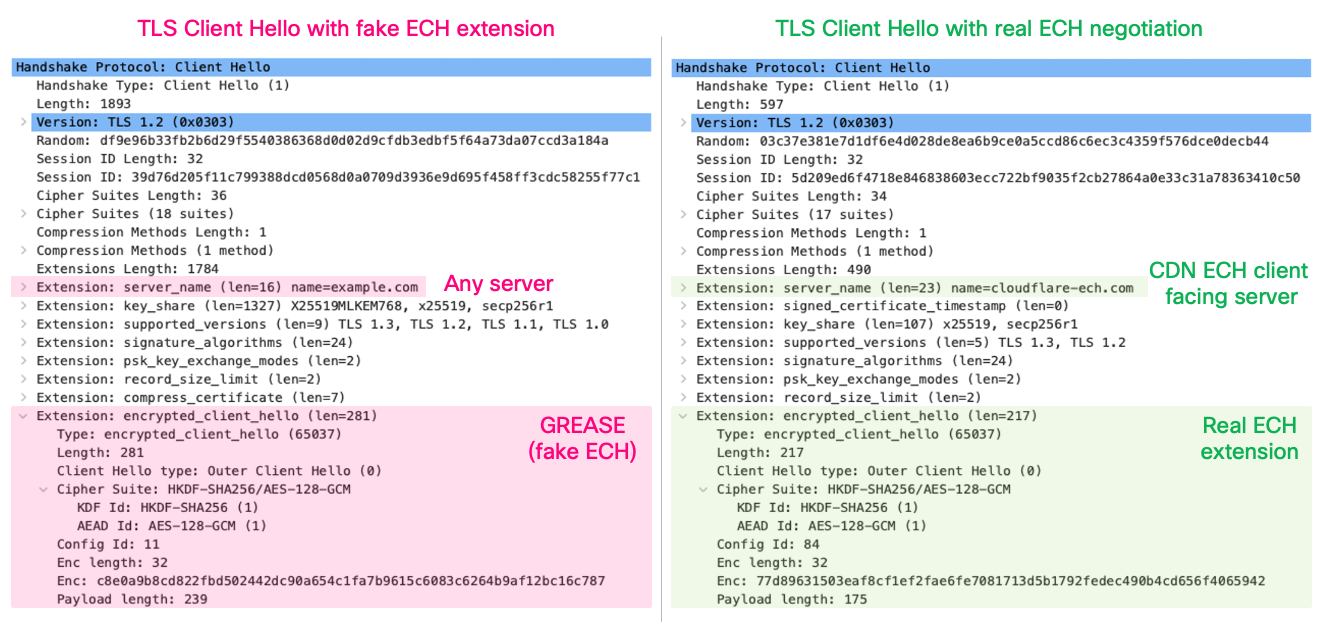

One of the most frustrating aspects of ECH for network security teams is the fundamental inability to distinguish real ECH connections from fake ones. This is not an oversight in the protocol design, but rather an intentional anti-discrimination feature built into ECH[5]. If a middlebox could reliably distinguish "ECH-capable connections" from "non-ECH connections," it becomes trivially easy to block, throttle, or classify encrypted-SNI traffic. By inserting fake extensions on every connection, the ECH standard mandates the clients to intentionally produce cover traffic. Therefore, browsers add a fake ECH extension all the time, even when:

- the target server does not support ECH

- the TLS connection is not really using ECH

- the client has no ECH configuration for the target server

Since all browsers send the extension, blocking ECH equals breaking most HTTPS websites, hence making attempt to selectively block only ECH connections impossible.

Below are two TLS Client Hello packets captured in Wireshark. One contains a genuine ECH extension with encrypted destination information. The other contains a dummy "GREASE" ECH extension that's just a placeholder. Both look identical to a firewall and there is no practical way to distinguish one for another. The structure of the fake extension faithfully reproduces the ECH payload with a dummy Cipher Suite, Config ID, and randomised pseudo-encrypted payload.

In theory you could search all DNS HTTPS records on the Internet and check if any of those entries has the ECH configuration matching this specific connection. Due to scale and dynamic nature of the DNS data such an approach is extremely hard to implement in real-time.

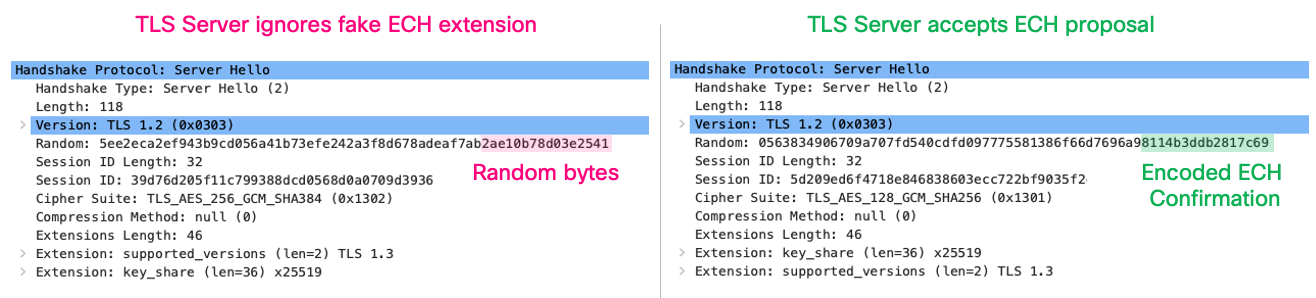

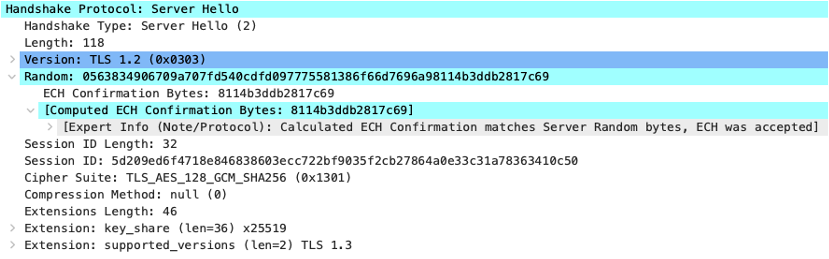

The protocol specification ensures the response from the server maintains uncertainty about whether Encrypted Client Hello negotiation succeeded. Below are two Server Hello responses to the Client Hello packets previously discussed: one where ECH was accepted, and one where it wasn't. They look exactly the same to a firewall or any other network middlebox device. These messages contain the standard TLS extensions provided by the server at this stage with no direct indication of ECH acceptance.

If a middlebox can't tell whether ECH was accepted, how does the client know? The client needs to understand whether ECH succeeded to determine if the connection is secure. The answer is securely encoded in the last 8 bytes of Server Hello's random value field. This encoding uses cryptographic techniques that only the client and server, who possess the corresponding HPKE private and public keys, can decode. The middlebox can't distinguish if these 8 bytes are random or were purposely encoded.

In the decrypted and decoded packet above, we can confirm that ECH was successfully accepted by examining the special encoding in the random value. But this information is cryptographically protected and invisible to middleboxes - only the client and server can verify it.

The Wireshark capture snippet above reveals that ECH was accepted since we collected pre-master-secret log file in a debug mode on the endpoint that initiated this connection. In normal circumstances this information is cryptographically protected and unavailable.

ECH is a nasty protocol from a security perspective but beautiful in its design - elegant cryptography, thoughtful anti-discrimination mechanisms and graceful fallback behaviour. Understanding how it works is crucial for building realistic defence strategies:

- You cannot distinguish real from fake ECH - browsers intentionally send dummy extensions everywhere

- Server responses don't help - ECH acceptance is cryptographically hidden from middleboxes

- Blocking ECH breaks the web - Since all browsers GREASE with fake ECH, blocking ECH means blocking everything

- The design is intentional - anti-discrimination is a core protocol goal

Understanding ECH's anti-discrimination design and detection challenges is essential context for the practical defence strategies that follow. While you cannot simply block ECH, Cisco Secure Firewall provides multiple capabilities that work together to maintain visibility and security despite these constraints.

Handling Encrypted Client Hello on Cisco Secure Firewall

How to recognize an ECH connection on the Firewall

Understanding what ECH looks like in your security logs is the first step to addressing the challenge. Let's examine how ECH connections appear in Cisco Secure Firewall and what patterns security teams should watch for.

In the example below, connectivity to the real destination "pig-in-the-middle.pl" server is explicitly denied in the firewall policy, nevertheless due to ECH the connection succeeds and by-passes the security rules.

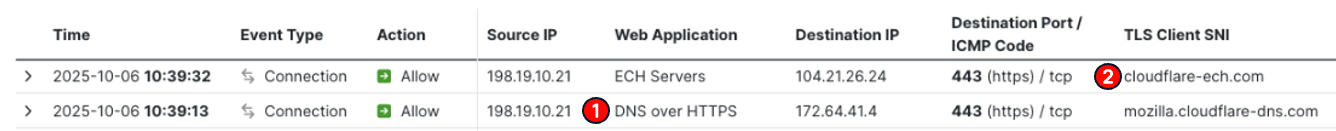

When a user connects to an ECH-protected website, you'll typically see a distinctive two-step pattern in your Unified Events Viewer:

- Encrypted DNS connection:

- The browser queries an encrypted DNS resolver (e.g. mozilla.cloudflare-dns.com) to retrieve the ECH configuration including the client facing server's public key.

- The firewall recognizes encrypted DNS traffic to a public resolver, but does not see what domain was queried (pig-in-the-middle.pl) or the ECH parameters returned.

- The ECH Connection:

- The browser connects to the CDN's client-facing server (e.g. cloudflare-ech.com) and establishes a TLS connection followed by application traffic exchange with the backend server (pig-in-the-middle.pl).

- Your firewall sees the Outer Client Hello SNI = cloudflare-ech.com but is not aware of the real destination (pig-in-the-middle.pl).

The connection to the prohibited destination is not blocked

Notice, there is nothing in the logs above indicating the actual website being accessed. The connection appears completely legitimate as routine traffic to a major CDN provider. The real destination hosted behind the CDN remains hidden from the firewall and the connection is immune to any URL category or AppID based access control rules.

Starting with VDB 416 (released October 2025)[6], Cisco introduced the "ECH Servers" Application ID detector. This allows firewalls to identify connections to known ECH-capable CDN providers, giving you visibility into which traffic is likely using ECH obfuscation. This detector matches traffic patterns associated with major CDN providers that offer ECH services, enabling you to:

- Monitor the volume of ECH traffic in your environment

- Create targeted policies for ECH-capable destinations

- Establish baseline metrics for ECH adoption trends

Do not block ECH traffic using firewall rules

Blocking ECH-capable CDN endpoints causes connection failures and extended timeouts with unpredictable behaviour across different browsers:

- Some browsers may display connection errors and refuse to fall back to cleartext SNI, effectively breaking access to the site entirely.

- Other browsers may retry multiple times with extended timeouts (15+ seconds per attempt), resulting in delays of up to 2 minutes before falling back.

This creates an inconsistent, degraded user experience across your organisation. Instead of blocking ECH connections, consider using the selective decryption downgrade approach described below, which achieves a fall back to clear text SNI outcome with much less impact to users.

Preventing ECH Configuration Bootstrap

The most effective defense against ECH is preventing clients from obtaining the ECH configuration in the first place. If the client never receives the ECH public key and parameters, it cannot use ECH - forcing a graceful fallback to cleartext SNI. ECH depends on DNS to distribute the bootstrapping configuration. Specifically, clients retrieve:

- The ECH public key (for encrypting the Inner Client Hello) along with HPKE encryption parameters

- The public name of the client-facing server

Without this information, browsers and applications cannot construct ECH-protected connections. This makes DNS visibility and control absolutely critical.

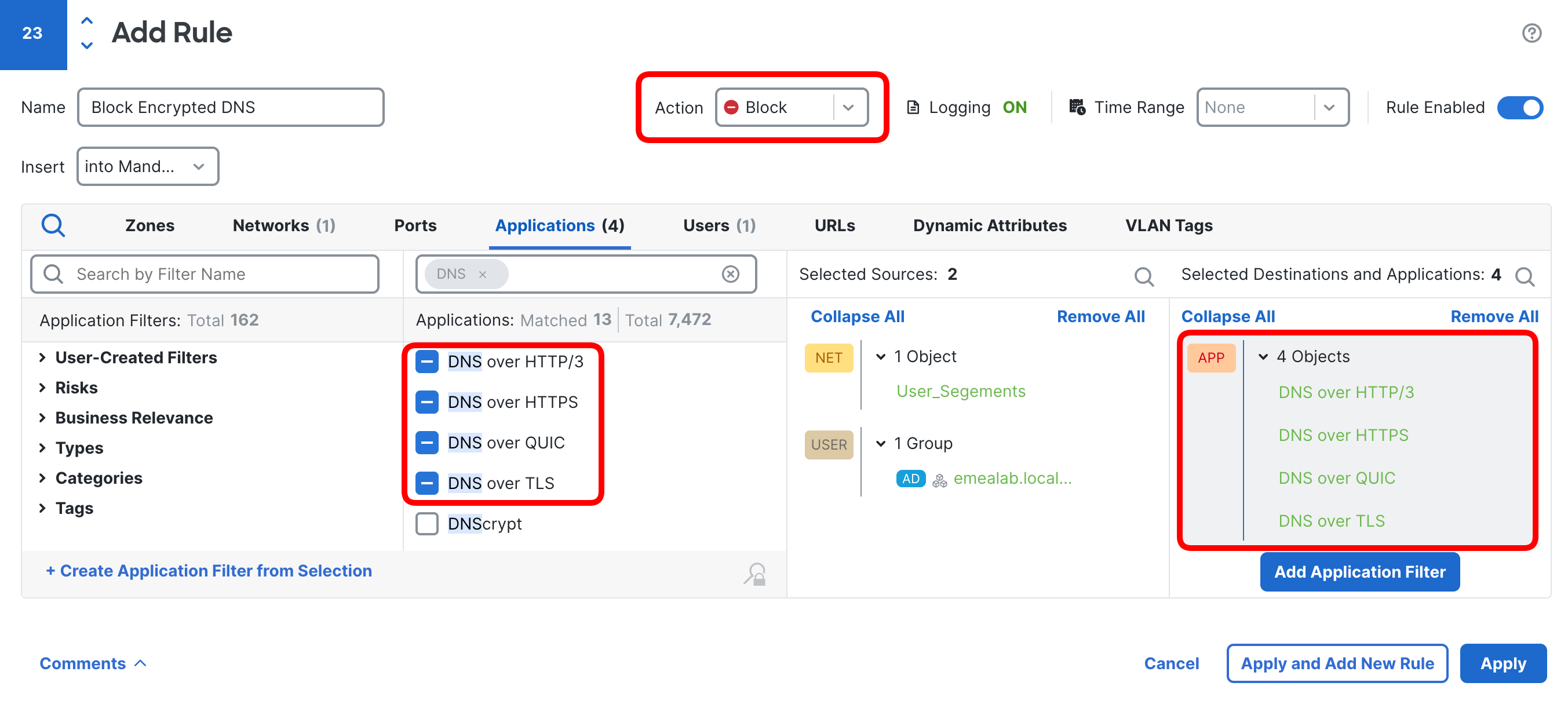

Cisco Secure Firewall includes application detectors specifically designed to identify and block encrypted DNS traffic.

You can match the following encrypted DNS protocols with application detectors:

- DNS over HTTPS (DoH)

- DNS over TLS (DoT)

- DNS over HTTP/3 (DoH3)

- DNS over QUIC (DoQ)

Important exception

If you use Cisco Umbrella, do NOT block the "DNS Crypt" application—this matches Umbrella's secure DNS service and would break your own security infrastructure.

Advanced threat actors can bypass DNS monitoring by hardcoding ECH configurations, retrieving them from alternative channels (blog posts, Youtube video descriptions, PasteBin.com, etc...).

This doesn't make DNS control worthless - it remains highly effective against:

- standard browser-based ECH usage (the vast majority of traffic)

- less sophisticated malware and threats

- opportunistic attackers relying on default browser behaviour

Think of DNS control as your perimeter fence stopping most ECH connections and increasing cost and effort for sophisticated attackers. With ECH volume reduced to minimum with strict DNS controls, you can focus on closely monitoring the remaining ECH connections with an increased likelihood of detecting malicious activity through unusual behaviours.

Intercepting ECH Connections via TLS/QUIC Decryption and ECH Stripping

When ECH connections reach your firewall, either because DNS controls were bypassed or because you're dealing with sophisticated threats, there's a technique on Cisco Secure Firewall available to trigger the ECH specification's "secure disable" mechanism.

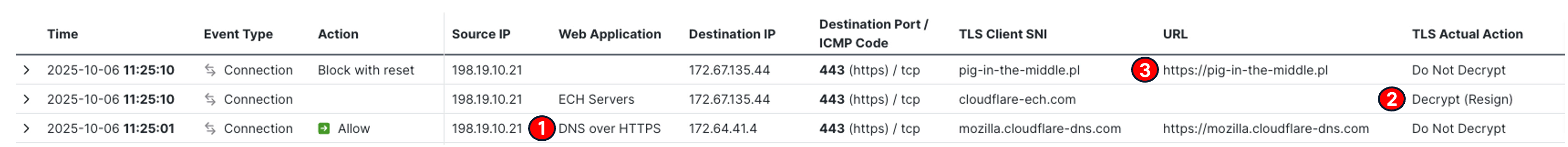

When the firewall performs TLS/QUIC decryption and strips the "encrypted_client_hello" extension from the connection, the client completes the handshake with the Outer Client Hello and regards ECH as securely disabled by the server. In this case the client terminates the initial TLS connection in which ECH was proposed and retries with a new TLS connection using clear-text SNI. Let's observe the evidence of this mechanism in the snippet from the Unified Events Viewer below.

- The first connection is encrypted DNS where the client learns the ECH configuration of the "pig-in-the-middle.pl" server.

- The subsequent entry logs the ECH connection to "cloudflare-ech.com" which the firewall intercepts and attempts to decrypt. Here is what happens under the hood:

- Client sends TLS Client Hello with the encrypted ECH extension protecting real target server identity

- Firewall decryption is configured to intercept and decrypt connections towards known ECH providers with "ECH Servers" AppID.

- Firewall decrypts this connection with key-resign method using InternalCA trusted by the client. This is a crucial step - the client must trust the certificate resigned by the firewall in the inspected handshake to consider ECH "securely disabled".

- Being inline in the TLS crypto handshake, the firewall strips the ECH extension when forwarding the TLS Client Hello to the "cloudflare-ech.com" server.

- Since there is no ECH extension in the handshake request, the ECH front-end server proceeds with the TLS handshake as if it was the actual target of the connection and ECH had not been offered by the client at all.

- The TLS handshake completes successfully and as per ECH specification, the client regards ECH as "securely disabled" by the server. This is because the server did not indicate successful ECH negotiation, nor provide fallback "ech configuration".

- Since the TLS connection could not reach the target server, the client does not send any application data and aborts this connection with "ech_required" alert.

- With ECH securely disabled:

- The client retries with a new non-ECH enabled TLS connection containing cleartext SNI and revealing the actual destination.

- This connection is correctly identified by the firewall and blocked by the policy as intended.

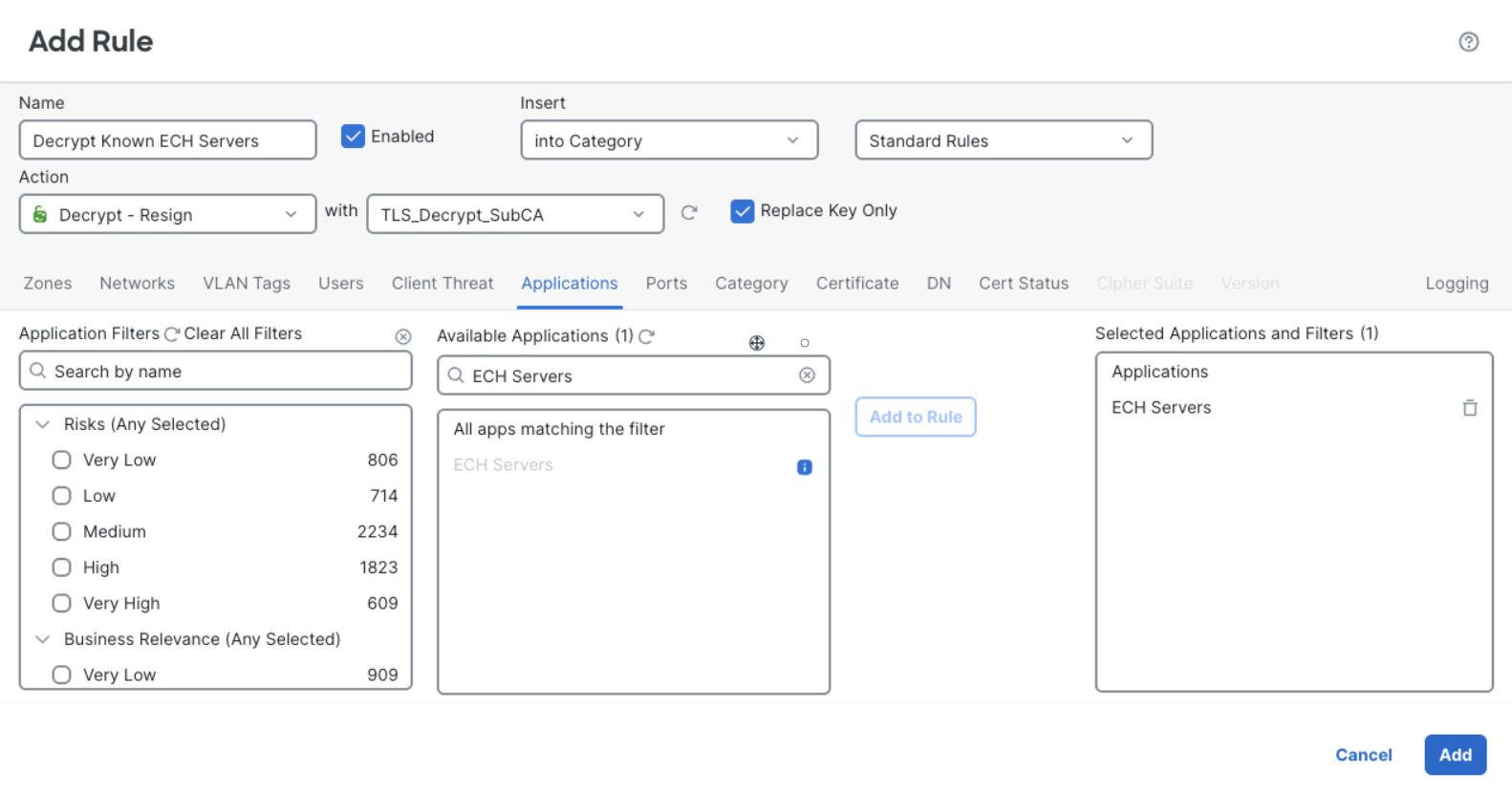

The figure below illustrates a sample configuration of a decryption policy rule that matches and decrypts connections to known ECH providers. Notice the rule is configured with "Decrypt - Resign" action and matches the "ECH Servers" AppID. The InternalCA object "TLS_Decrypt_SubCA" that the firewall uses to spoof target server certificates must be trusted by the endpoints attempting ECH connections.

The flexible decryption capabilities of Cisco Secure Firewall combined with the "ECH Servers" AppID allow you to apply policy exclusively to ECH traffic towards known CDNs. The downgraded cleartext SNI traffic that follows will now be visible to the firewall for access control and inspection. This approach allows you to:

- Restore visibility without full payload inspection overhead.

- Apply URL filtering and reputation checks on revealed destinations.

- Make informed selective decryption decisions on the actual targets.

- Optimize performance impact while maximizing security effectiveness .

This approach provides visibility restoration through ECH downgrade, with the flexibility to inspect only high-risk destinations after they've been revealed.

This technique only works if the client trusts the firewall's replacement certificates. It is not applicable to guest devices where you cannot install your internal CA in the trusted root certificate repository.

Detecting suspicious activity in ECH connections with Encrypted Visibility Engine

Even when ECH successfully hides the destination and decryption isn't deployed, Cisco's Encrypted Visibility Engine (EVE) provides a critical capability: identifying who is making the connection, even when you can't see where it's going. EVE analyses TLS and QUIC handshake fingerprints by examining the encrypted traffic and the Outer Client Hello - without requiring decryption.

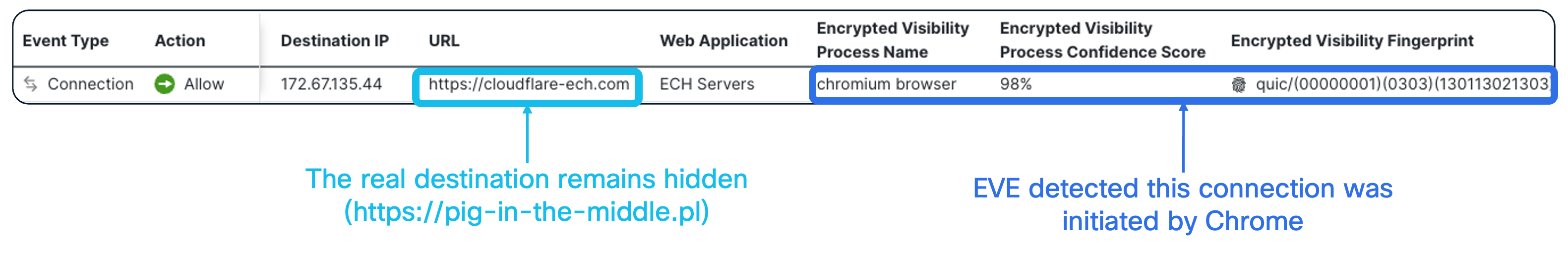

In the example below we can see an ECH connection established with the "cloudflare-ech.com" SNI and an EVE fingerprint showing "chromium browser". Notice, the Encrypted Visibility Engine does not discover the actual target of the connection. The real server "pig-in-the-middle.pl" remains hidden.

Let's have a closer look at the value provided by the EVE's source process fingerprinting. From a security standpoint, ECH connections originating from users' browsers are primarily a visibility problem. Administrators can't enforce their content filtering policies when destinations are hidden, and the Encrypted Visibility Engine does not solve that problem.

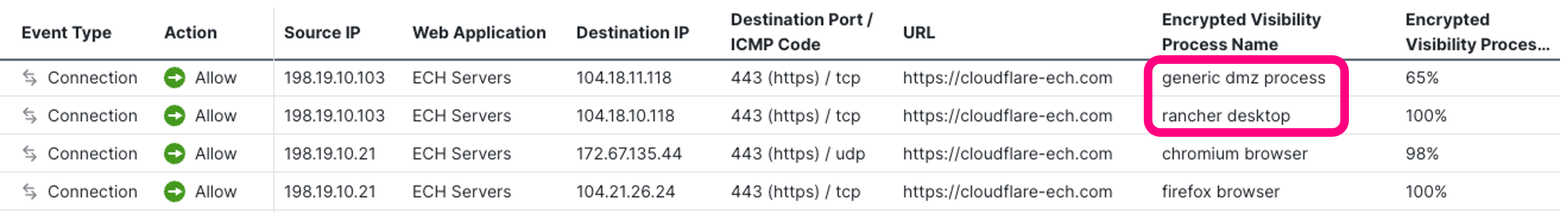

While we've lost visibility into the destination, the EVE fingerprint with the source process provides valuable context. The more serious danger is when ECH is used by malware as a command-and-control (C2) channel. ECH is going to be generated, in most cases, by most popular browsers with their baked-in capabilities. However, if you see something unusual connecting with ECH to CDN providers, that's something fishy and worth investigating. In such cases, EVE can help us distinguish connections generated by common browsers (recognised as Firefox, Chrome, Edge, etc.) from malicious processes like ECHidna, discussed earlier. In the figure below you see four connections - two originating from Firefox and Chrome, and two issued by other non-standard processes "generic dmz process" and " rancher desktop".

Without Encrypted Visibility Engine, connections in the log above would all appear to connect to "cloudflare-ech.com" and remain undistinguishable from each other, hiding a threat under the radar. With Encrypted Visibility Engine, browser connections are properly fingerprinted to Chrome and Firefox and non-standard processes are detected, disclosing anomalies and allowing security teams to react.

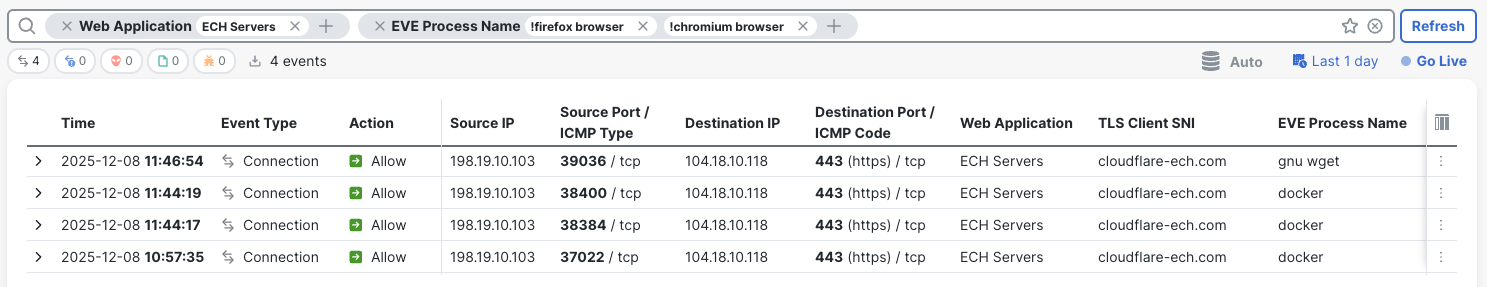

You can easily pin-point the suspicious connections in the Unified Events on the Firewall Management Center. Set the filter to match the "ECH Servers" AppID and exclude EVE Process Names of popular browsers, e.g. "!firefox browser" and "!chromium browser". The screenshot below shows this filter returning four suspicious connections originating from "docker" and "gnu wget" processes.

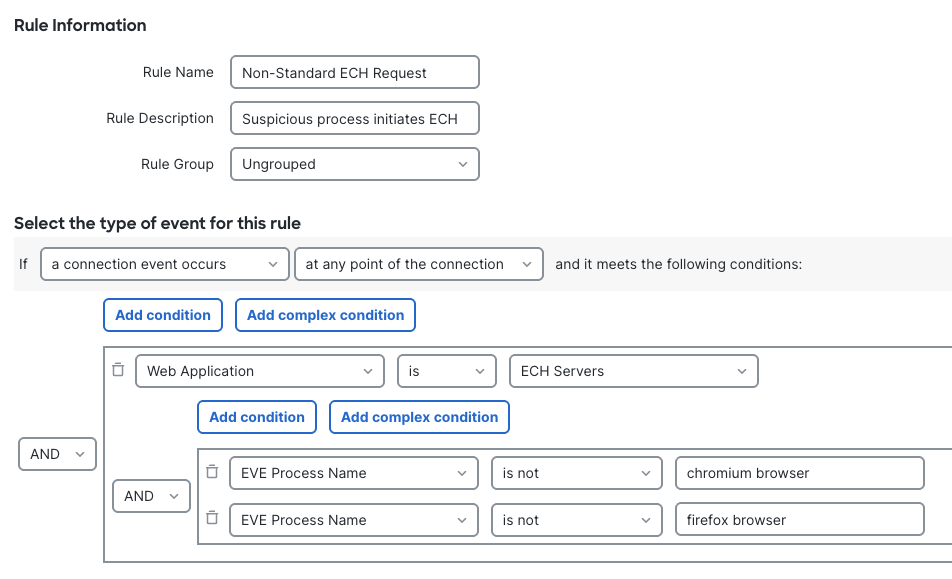

Rather than manually reviewing connection logs, you can automate the detection of suspicious ECH usage with Cisco Secure Firewall's correlation policies. The sample correlation rule illustrated below triggers as soon as the firewall logs a connection towards a known ECH Server that has an EVE fingerprint other than a common Chrome or Firefox browser. You can configure your Management Center to send an email or Syslog alert when the rule matches, or run an automated remediation action. This reduces the manual log review burden with near-real time alerting capabilities.

Cisco's Encrypted Visibility Engine provides insights into the binary executed at the endpoint level — information normally available only to endpoint security products. EVE identifies who is making ECH connections even when the destination remains hidden, distinguishing legitimate browser traffic (Chrome, Firefox, Edge) from suspicious non-browser processes like malware C2 channels.

The Encrypted Visibility Engine provides a crucial and unique capability in the era of the new crypto stack where traditional visibility methods fail. All of this intelligence is available with minimal performance impact since EVE does not require decryption and relies only on a single packet lookup during the TLS/QUIC handshake.

Cisco Secure Firewall allows you to detect and automate responses to threats that would otherwise remain completely invisible beneath the ECH obfuscation layer by using the Encrypted Visibility Engine, the "ECH Servers" AppID, and the correlation policy.

Three Layer Protection Approach

ECH breaks most traditional security controls. You cannot rely on URL filtering, you cannot see the destination, and simply blocking ECH traffic creates an unacceptable user experience. Most browsers have the ECH infrastructure built in, and adoption will grow every day. But you are not powerless if you prepare accordingly. We recommend constructing three layers of defence that work together to maintain visibility and security despite ECH's sophisticated obfuscation:

- Layer 1: DNS Control- prevent clients from learning ECH configuration.

- Layer 2: Endpoint Management- disable ECH and encrypted DNS at the source.

- Layer 3: Selective Decryption + Behavioural Detection - downgrade remaining ECH and detect anomalies.

Each layer addresses ECH at a different stage: before configuration is obtained, at the endpoint level, and during connection establishment. This approach provides a progressive defence that significantly reduces ECH's impact on your security posture.

Layer 1 - DNS Control

The most effective defense against ECH is preventing clients from obtaining the ECH configuration in the first place. DNS is the primary way of distributing the bootstrapping ECH configuration. If there is no configuration shared, the client will naturally fall back to cleartext SNI.

- Configure DNS filtering to prevent ECH bootstrap even when using approved corporate DNS. If your DNS infrastructure supports it, configure your DNS resolver to:

- Strip ECH parameters from HTTPS records entirely.

- Block HTTPS records for known ECH-enabled domains.

By standard, ECH configuration shouldn't be provided over cleartext DNS. However, it might happen, which is why scrubbing HTTPS records provides an additional safeguard beyond just blocking encrypted DNS protocols.

- Block the "canary domain" - configure your DNS resolver to block "use-application-dns.net". This special domain tells browsers whether they can use encrypted DNS protocols. Blocking it signals browsers to respect system DNS settings and not attempt DoH/DoT/DoQ.

- Use Cisco Secure Firewall's application detectors to identify and block encrypted DNS protocols at the firewall:

- DNS over HTTPS (DoH)

- DNS over TLS (DoT)

- DNS over HTTP/3 (DoH3)

- DNS over QUIC (DoQ)

- Create firewall rules allowing approved DNS resolvers only - ensure all DNS queries flow through your controlled, filtered infrastructure:

- allow DNS port 53 UDP/TCP to your corporate DNS servers

- block all other DNS traffic to any destination

- prevent clients from reaching public resolvers (e.g. 1.1.1.1, 8.8.8.8 etc...)

Consider DNS control as your perimeter fence, assuming a more determined adversary could hardcode ECH configuration in malware. Alternatively, they could use the ECH recovery mechanism to provide up-to-date ECH configuration directly by the server or retrieving it from alternative channels (e.g. blog posts, social media, GitHub repositories etc...).

Layer 2 - Endpoint Management

If you have control over your endpoints you can disable ECH and encrypted DNS directly in browser settings. This is your second line of defence that works at the client level.

- Deploy browser policy templates - use configuration management tools to deploy browser policies disabling encrypted DNS protocols, the use of real ECH in the handshakes, and respect the OS DNS settings.

- Lock the settings- prevent users from re-enabling encrypted DNS or ECH through browser settings. This ensures policies remain enforced even if the user attempt to bypass them.

- Deploy the above rules wherever possible - to all managed, BYOD, and contractor devices.

This approach further reduces ECH footprint in the network originating from managed endpoints but does not work for guest devices, unmanaged IoT and sophisticated malware ignoring browser policies.

Layer 3 - Selective Decryption + Behavioural Detection

With the two first steps: DNS control and endpoint policies, you massively reduce the amount of ECH traffic. With DNS based ECH bootstrap impaired and endpoints configured not to use ECH, clients naturally fall back to cleartext SNI. As a final safeguard, use selective TLS/QUIC decryption to downgrade any remaining ECH connections, and monitor traffic with Encrypted Visibility Engine to detect any anomalous behaviour.

- Configure selective decryption for known ECH providers - apply a "Decrypt - Resign" decryption rule matching the "ECH Servers" AppID to trigger a graceful downgrade to cleartext SNI. When decrypting the connection the firewall strips the ECH extension from the initial request, tricking the client to "securely disable" ECH.

TLS handshake interception to strip the ECH extension is a contributor to overall decryption load on the firewall despite no application data being exchanged between the client and the server. The complexity of becoming a man-in-the-middle requires establishing two separate TLS connections and generating key-pairs in real-time as with any other connection decrypted by the firewall.

When applying this technique selectively to "ECH Servers" monitor the load on your firewall and ensure the ECH traffic volume has already been trimmed by DNS filtering and the endpoint management discussed above.

This technique takes advantage of a weak point of ECH applicable only when the user machine trusts firewall spoofed certificate. This will not work in guest networks or if the client doesn't trust your firewall.

- Detect unusual ECH connections with Enable Encrypted Visibility Engine - hunt for suspicious connections to known CDNs originating from non-browser endpoint programs. Focus on ECH connections generated by unknown binaries.

EVE provides a unique capability in your security toolkit against the ECH challenge not available from any other firewall vendor - insights into the binary executed at the endpoint level, information normally available only to endpoint security products.

Selective decryption downgrades ECH on managed devices with certificate trust while EVE monitoring allows you to detect anomalous ECH usage on any remaining connections that could not be tricked to switch to clear text SNI.

Your Defence Strategy Summary

The three-layer approach doesn't eliminate ECH, but it transforms an impossible problem into a manageable one. You cannot stop ECH entirely, but you can control its distribution, disable it where possible, downgrade it when necessary, and detect when it's being abused. Together, these three layers provide comprehensive defense against ECH-enabled threats—both today and as adoption accelerates tomorrow.

Disclaimer

The recommendations, techniques, and defence strategies described in this article were tested and validated at the time of writing (December 2025). However, readers should be aware of the following important considerations regarding implementation variability:

- Encrypted Client Hello (ECH) is currently at draft version 25 and has not yet been officially ratified as an IETF standard. While the protocol is mature and widely implemented, future changes to the specification may occur before final standardisation. Any modifications to the ECH standard could impact the effectiveness or applicability of the defence strategies outlined in this document.

- Not all techniques described in this article may work universally across all combinations of browsers, browser versions, CDN providers, and infrastructure components. Organisations should thoroughly test these approaches in their specific environment before relying on them for production security controls.

While these techniques have been validated in controlled environments and represent current best practices, Cisco makes no guarantee that these approaches will remain effective indefinitely or work in all deployment scenarios.

Security teams should treat these recommendations as starting points for developing comprehensive ECH defence strategies tailored to their specific organisational requirements and risk tolerance.

📚Additional Resources

Cisco Live! Session:

References:

[1] - ECH: Hello to Enhanced Privacy or Goodbye to Visibility?

[2] - Top 100K Websites with ECH enabled on 2025-07-08 (by Divested Computing)

[3] - Browser Share Statistics (by stetic)

[4] - Stealth over TLS: the emergence of ECH-based C&C in ECHidna malware

Updated 3 months ago